What is the human rights situation in the Philippines? The “war on drugs”, declared by former President Rodrigo Duterte, has cost the lives of countless people. During his 6 years in power, 220 human rights activists were killed and the government launched smear campaigns against anyone who dared to speak out: Journalist Maria Ressa and my former partner in the parliamentary solidarity programme Sarah Elago were victims of these campaigns.

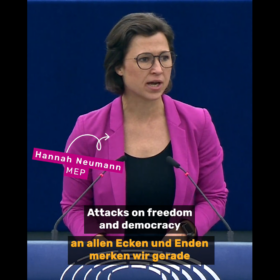

In May last year, Ferdinand Marcos junior was elected president. Will the situation improve with the new government? That’s what a delegation from the European Parliament’s Human Rights Committee wanted to find out during a trip in February – I was the head of the delegation.

During the trip, we had a busy programme: we met with members of the Senate and House Committees on Justice, various ministers, members of the Commission on Human Rights, representatives of the United Nations, civil society organisations, trade union representatives and journalists.

One of the topics was the re-accession of the Philippines to the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court. For me, this would be an important step towards ensuring that the Philippines can continue to rely on privileged trade relations with the EU, given that the so-called GSP+ trade system is linked to progress on human rights. Indeed, President Marcos has announced that the so-called “war on drugs” will focus more on prevention and rehabilitation in the future. But there are still reports about extrajudicial executions, and the executions of recent years are being dealt with very slowly, if at all. It is especially important to investigate each of these cases and bring those responsible to justice.

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from X. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationLeila de Lima: “I finally want to be free!”

“Red tagging (the practice of branding individuals and/or organisations as leftist, subversive, communist or terrorist and thus “enemies of the state”) remains widespread in the Philippines and is used to silence critics. During our meetings, we called for an effective end to this method – and we pointed out that there is an urgent need for an ambitious law to protect human rights defenders.

Another subject of our discussions was the continuing discrimination against women and girls (including with regard to sexual and reproductive rights) and the rights of indigenous peoples. One topic here was access to land and efforts to resolve conflicts in Mindanao – this region is particularly familiar to me because I did research there for my doctoral thesis in 2009 and also repeatedly visited the area later on.

Visiting ex-senator Leila De Lima in prison was particularly important to us. The former senator has been imprisoned for six years now based on fabricated charges. She was one of the first to criticise former President Duterte for his “war on drugs” and called for international investigations to be launched. More and more allegations against her are falling apart, key witnesses have testified (following the change in government) that their incriminating statements are baseless and were made due to external pressure. We demanded the immediate and unconditional release of Leila De Lima and all other political prisoners. And she herself said, “It’s time for me to be free now!”

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from X. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More Information“Hold the Line”: Visit to Rappler

Another highlight for me was the visit to Rappler. The media company, founded by Maria Ressa, had been the first to report on Duterte’s so-called “war on drugs”. Since then, Maria Ressa and Rappler journalists have been harassed and subjected to “red tagging” accusations. Therefore, “Hold the Line” has become Rappler’s slogan: The platform wants to continue its resistance against attacks and interference in its reporting, as well as its fight against fake news and disinformation. We were very impressed by the work of all those fighting for press freedom in the Philippines – and I left a little message for them:

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from X. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationIt became clear during our visit: The new government is clearly more open to discussing issues of human rights and press freedom. This is definitely an encouraging sign – but whether concrete changes will follow remains to be seen. Many of the civil society actors we met were sceptical, also because of their experiences in the past years.

As a delegation, we called for measures to combat impunity, to protect human rights defenders and for the implementation of international labour standards and human rights agreements – and offered EU technical support and meetings to exchange experiences with regard to the agreements. The National Human Rights Commission already supports the reappraisal of the extrajudicial killings, and more cooperation is certainly possible.

Interest of the press in our visit was strong. I was particularly pleased to give an interview to ABS-CBN News. The station lost its broadcasting licence under Duterte and has yet to get it back. You can watch it in full here:

You are currently viewing a placeholder content from X. To access the actual content, click the button below. Please note that doing so will share data with third-party providers.

More InformationThe Human Rights Committee’s press release on our visit can be found here. We will take up the issues in a meeting in the coming weeks and will continue following the developments. I would also like to thank my colleagues Isabel Wiselar-Lima, Karsten Lucke, Silvia Sardone, Ryszard Czarnecki and Miguel Urban Crespo who travelled with me for their collegial cooperation, as well as the EU delegation in Manila and its ambassador Luc Veron.